When You’re Finished Changing, You’re Finished

No, Facebook doesn’t decide whether Internet comedy lives or dies.

This week, an article in Splitsider featured an interview with a comedy writer who had just been let go from Funny Or Die. He tweeted: “Mark Zuckerberg just walked into Funny or Die and laid off all my friends.” In the interview he bemoaned that Funny Or Die used to have “success in more predictable systems” and that “Facebook has created a centrally designed internet. It’s a lamer, shittier looking internet. It’s just not as cool.”

Indeed, Facebook’s News Feed algorithm shift has negatively affected the referral traffic that publishers receive. However, one should avoid romanticizing the internet of the past as a freely democratic utopia. Over the last 20 years, the centers of internet power have shifted innumerable times (for example, AOL used to charge $1 million to own a custom keyword on its closed platform, and people paid it because they needed that important distribution channel). Since the Web became mainstream, its dynamics have unquestionably destroyed thousands of traditional industries both in media and elsewhere (magazines, newspapers, retail, travel agents, alarm clocks, flashlights, to name but a few).

In digital media, change is the natural order, and people have two choices: allow themselves to be run over while complaining about how unfortunate it is, or adapt quickly and do their best to survive.

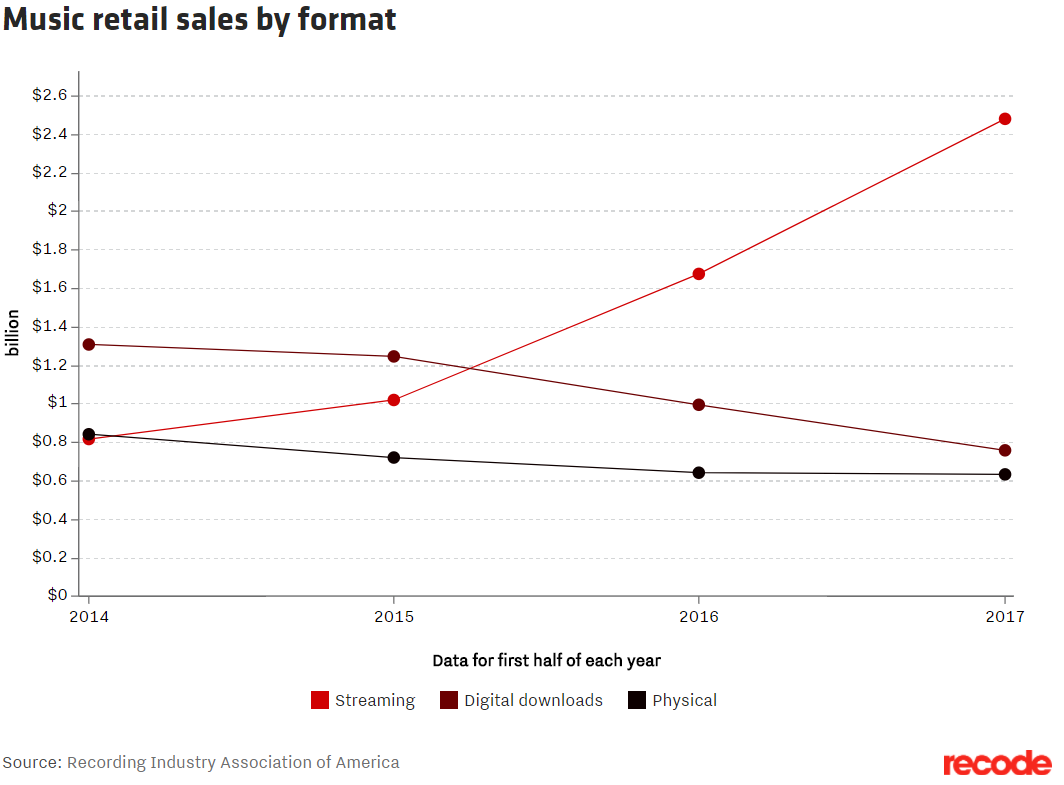

An excellent example is the music business, which resisted change for a long time. However, as music companies have finally embraced the streaming subscription world, they have seen revenues begin to grow again. (There are certainly arguments about whether artists should be making more than they are currently, but the ecosystem is least healthier than it has been in two decades.) Once those companies accepted the new paradigm of how consumers wanted to listen to music, they realized that people will indeed pay for something they find valuable. Suing copyright infringers did not turn their fortunes around; finding ways to work alongside their customers sensibly did.

The same principle applies to distributors. For example, as Comcast sees consumers cut the cord for traditional video offerings, the company has begun to invest to diversify its offerings. They added the ability to watch Netflix and YouTube through their set-top boxes; launched a mobile carrier offering (which now has almost 400,000 subscribers); and introduced their own skinny bundle. It may take a while for them to replace their lost revenue, but they understand that consumer behavior is morphing, and they are working aggressively to cater to it.

If Funny Or Die looks to different distribution channels to survive because Facebook has figured out for the moment how to control one marketing pipe, that’s simply FoD being smart. And the creators who were used to making content for one medium need to learn how to adapt to the new ways audiences want to be entertained (while ensuring those ways are commercially sound).

Building a business on someone else’s back, Facebook’s or anyone else’s, is a flawed and careless strategy. Already, many savvy publishers have figured out ways to rescue themselves from over-reliance on the Facebook algorithm, and other smart ones planned for that from the beginning. In short, there will always be dominant distribution channels, but content creators need to continue to ride above the platforms and remain nimble enough to keep control of their own destiny.

Finally, companies need to understand the business they are in. Funny Or Die’s comedians are not in the internet business. They are in the funny storytelling and content creation business. Determining how to tell jokes multiple ways for audiences who interact differently with individual platforms leads to successful growth instead of obsolescence. As Benjamin Franklin wrote, “when you’re finished changing, you’re finished.”